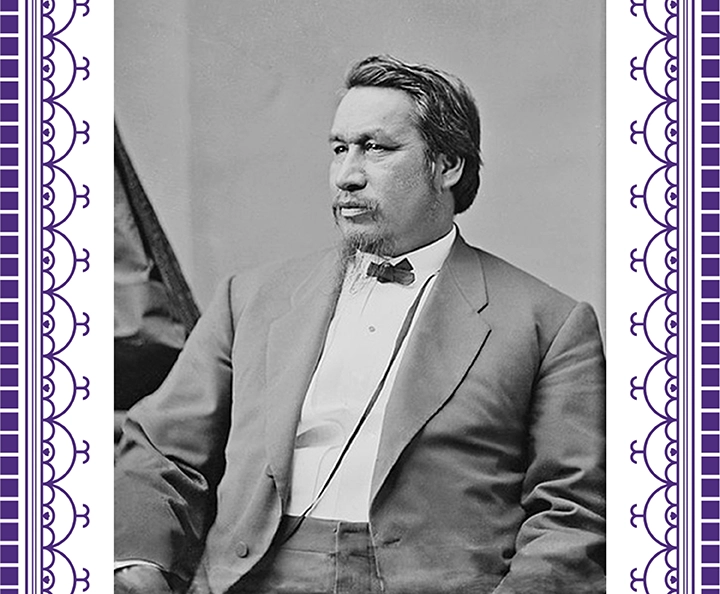

Parker was denied admission during his lifetime because he was Native American

Buffalo, NY – November 14, 2025 – According to American Bar Association data from 2022, of the 1.3 million attorneys in the United States, only 0.5% were Native American. This means that there are only approximately 6,500 Native American attorneys in the entire United States. Today, there is one more.

In a historic action, the New York Appellate Division, Fourth Department, granted the posthumous bar admission of Ely Samuel Parker, a highly accomplished Seneca leader, Civil War general, and a fierce advocate for his people. Parker is the first Native American posthumously admitted to the bar in United States history, and one of a small number of aspiring attorneys of color to ever be so honored.

Parker was a trailblazer whose influence and advocacy for Native American rights shaped the course of history not only for the Seneca people and all Native Americans, but also for the United States. His long overdue admission marks a major step forward toward equity in the legal profession and rectifies his shameful denial from practicing law in the 1840s solely because, as a Native American, he was not considered a U.S. citizen.

“Today, Ely S. Parker joins the ranks of admitted Attorneys at Law, righting the historic wrong of denying him the opportunity for admission due to the fact he was Native American,” said Justice Mark A. Montour, Associate Justice for the Appellate Division, Fourth Department.

“Ely Parker’s posthumous bar admission is the first step in the long march for justice for Native people,” added Lee M. Redeye, a Seneca attorney and Deputy Counsel for the Seneca Nation of Indians, who helped lead the effort for Parker’s admission. “This historic event not only rights a profound wrong from our past but also serves as a powerful example for future generations of Native attorneys by showing them that we do not have to accept injustice. We can, and we will, fight for our people, for our nations, and for our future generations.”

Born on the Tonawanda Seneca Reservation in Western New York, Parker’s achievements spanned engineering, diplomacy, military service, and public administration.

As a young man in the 1840s, Parker “read the law” for three years in the Ellicottville law offices of Angel and Rice. Despite completing his training and meeting all the requirements for admission to the bar, he was never admitted to practice law in New York because at that time only natural-born or naturalized citizens could be admitted. Native Americans would not be granted U.S. citizenship until the Citizenship Act of 1924, decades after Parker’s death. Despite this ironic injustice, Parker played a pivotal role in protecting Seneca lands through successful lawsuits that included victories in the New York Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Parker’s legacy was etched into American history when he served in the U.S. Army as a military secretary to General Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War. In one of his many monumental achievements, Parker drafted the terms of surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Appomattox Courthouse in 1865. In recognition of his honorable and meritorious service during the Civil War, Parker was brevetted brigadier general. He would later fight to implement reforms aimed at improving U.S.–tribal relations when President Grant appointed him to serve as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the first Native American to hold that position. Parker’s distinguished service and contributions to the United States make his denial into the New York State Bar a stark reminder of the systemic barriers faced by Indigenous people.

Parker’s posthumous admission to the bar is the culmination of a years-long effort that is both historic and deeply personal. John G. Browning, former justice, Texas Fifth Court of Appeals, initially contacted Al Parker, a direct descendant of Ely Parker, with the concept. They worked together on the effort for several years before Al Parker’s passing in 2022. Al Parker’s daughter, Melissa Parker Leonard, then helped carry the effort forward.

“Ely Parker’s denial from the New York State Bar was not just prejudice, it was part of a larger strategy of legal exclusion that sought to remove Seneca people from their land, and those consequences were generational,” Parker Leonard said. “My father dedicated his life to preserving this history and ensuring it would never be forgotten. Correcting the record is an important step toward acknowledging past wrongs, because when injustice is named, healing can begin.”

In addition to the leadership of Browning, Redeye, Parker Leonard, and Montour, the effort for Parker’s posthumous bar admission was further supported by the National Native American Bar Association, the Native American Rights Fund, the Minority Bar Association of Western New York, the U.S. Department of the Interior, the National Park Service, the Buffalo History Museum, the Appomattox County Historical Society, renowned author Laurence M. Hauptman, the Western New York Civil War Society, and the Echoes Through Time Learning Center.

Parker’s posthumous admission follows similar actions in New York State, underscoring the New York Court System’s commitment to acknowledging past injustices in the legal system and taking meaningful corrective measures. It also serves as a reminder of the progress made since the 1840s and sheds light on the ongoing efforts to address the lack of Native American representation in the legal profession.

“Ely Parker’s admission not only rights a historic injustice to him, his family, the Seneca people, and Native Americans everywhere, it shows that justice has no expiration date,” said Browning. “It is always the right time to do the right thing.”