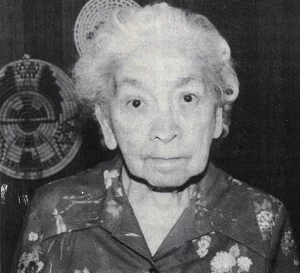

Cordelia G. Abrams, First Seneca Nation Employee

Cordeila Abrams was the first Seneca Nation employee. Before the 1950s, the Nation did not have dedicated office space for Seneca Nation Executives. Following council sessions, the Clerk carried around important documents in brief cases and boxes and stored them at home.

Cordelia managed the first official Seneca Nation office and took on the job of organizing, recording, and documenting Seneca Nation meetings and all other clerical work singlehandidly.

She worked closely with Dr. Arthur Morgan during the turbulent years of the Kinzua Dam.

Cordelia was a educational pioneer. Her contributions and dedication to the Seneca Nation are unmatched. Cordelia deserves to be remembered for the next seven generations of Seneca women.

Cordelia Abrams of Horseshoe Celebrates her 91st Birthday

Republished from The Orator 1989, courtesy of the Seneca Nation Archives

Born and raised in Horseshoe and now retired to her old homestead at the eastern end of the Allegany Reservation. Cordelia Abrams celebrated her 91st birthday on Saturday, January 21.

Cordelia’s parents were Henry and Emiline Lucy [Jimerson] John. Her father worked on the railroad and her mother later became a practical nurse.

“Just a bad kid” is how she recalls her childhood. Being at the tail end of the reservation there were not too many other children to play with except her sister, Edith Daly. Cordelia explained there seemed to be a separation from the rest of the reservation, because her community is between the City of Salamanca and the end of the reservation.

She graduated from the eighth grade at the District School #6 and went on to finish at Salamanca High School, Class of 1917. Cordelia was the first Indian in New York to finish at a district school and go on to graduate from high school.

Having saved $60.00, a hefty sum in those days, Cordelia rode the train to Jamestown where she enrolled herself at Jamestown Business College. Although her dream was “to be a nurse in the worse way” and having already devoted three years to studying Latin to help her in the medical profession, she chose Jamestown because it’s close to the proximity of the reservation.

She remembers well her arrival in Jamestown and going straight to the school to enroll. She then went to the “YW” where she had heard there were a room for young girls, but the YWCA was filled. With the help of the desk clerk, Cordelia ended up going to the home of a Jamestown family where she stayed for eight years. Her days were spent in the class-room and during the evenings she cared for the couple’s two children. Cordelia laughs about being taken in by the family “sight unseen.”

Her first job came when the woman with whom she was staying told her the secretary at a family business, Sherman Brothers Upholstery Co., was ill and could not work. Asked if she was interested in helping out. Cordelia went to work. The secretary never returned to the company and Cordelia remained in her position for nine years later. Not one to give up, Cordelia had graduated from JBC in 1919 by keeping up with her studies on Saturdays.

Oliver, an “Allegany boy,” and Cordelia were married at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Jamestown.

Expecting their first child, Cordelia’s father urged them to return to the family home on Allegany to have the child. It was Dr. Taggert and a nurse who assisted with the birth of Oliver Jr., the first of five children born to Oliver and Cordelia.

Life on the reservation wasn’t easy, but Cordelia remembers “nobody would ever want to go on welfare” in those days. She recalls they always had enough to eat, because everyone raised crops and stored away for the winter months. Cordelia said, “Ma used to always say March was the hardest month on the year because everything was going.”

She remembers her mother canning 400 jars of foodstuffs and there were always bins in the root cellar filled with potatoes.

Folks raised pigs and cows too. There was one particularly warm fall when the goods stored away didn’t freeze. So upon advice of her mother, she went to the local meat market to sell a pig. She assured the butcher the pig did not weigh less than 400 pounds. When her husband took the butcher into the barn to view the pig, Oliver turned to tell Cordelia, who was standing nearby, “If it weighs more than 125 pounds, you’ll be lucky.” She laughingly recalls, “It looked good to me!”

On another visit to the same butcher to sell a calf, the butcher asked her what kind of cow she was selling. Not very knowledgeable on that subject, Codelia responded, “it’s a girl calf.” That was the end of farming for Cordelia.

Sewing bees were common in those days. Cordelia recalls a quilting bee at her grandmother’s log cabin. Just a child, she asked her grandmother if she could have the quilt when she died. “Gyoh ho!” was her grandmother’s reaction to the hexing question.

Cordelia credits her late husband Oliver, a boilermaker who dies in 1958, with encouraging their children to become professionals by keeping “tabs on them.” She is concerned that today parents do not take enough interest in their kids. Oliver, Jr., works for the U.S Department of Education and lives in Alexandria, Virginia. Allan lives in Batavia and works at the Alba School District and teaches part-time at Attica Correctional Facility. Carol has been a nurse for 25 years at Buffalo’s Children’s Hospital. George resides on the Allegany and devotes his energy to the Iroquois National Museum. Dale, who was a registered nurse, died in 1988.

Cordelia devoted many years to working in the Indian office that was created by President Roosevelt’s Emergency Conservation Act and continued to do so after the Seneca Nation took over the office. She singlehandedly preformed all the clerical duties of the Nation. She believes the Kinzua years were the most interesting. She especially remembers working with Dr. Arthur Morgan who designed an alternative Conewango plan that would have been better environmentally and better for the Senecas than the Kinzua plan of the U.S Army Corps of Engineers. After leaving the Nation in 1959, Cordelia went to work in the placement office at Buffalo State Teachers College from which she retired at the age of 65 years.

When asked how she celebrated her 91st birthday, she responded “with cake and ice cream.” Then she proudly pointed to the new dining table and chairs that was a present.